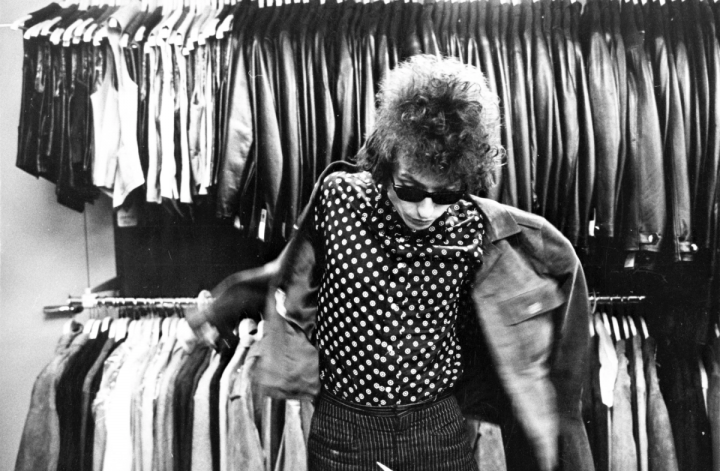

Blonde on Blonde is, arguably, Bob Dylan’s most iconic album. Granted, that’s an easy argument to make for any Bob Dylan album. But for more than half a century on, Blonde on Blonde remains a crucial addition to musical history, pop culture and the 1960s New York music scene, that makes Blonde on Blonde an album that simply cannot be described as anything other than a masterpiece.

This essay was originally written in 2016, in response to Blonde on Blonde turning 50.

Bob Dylan’s undisputed 1960s classic

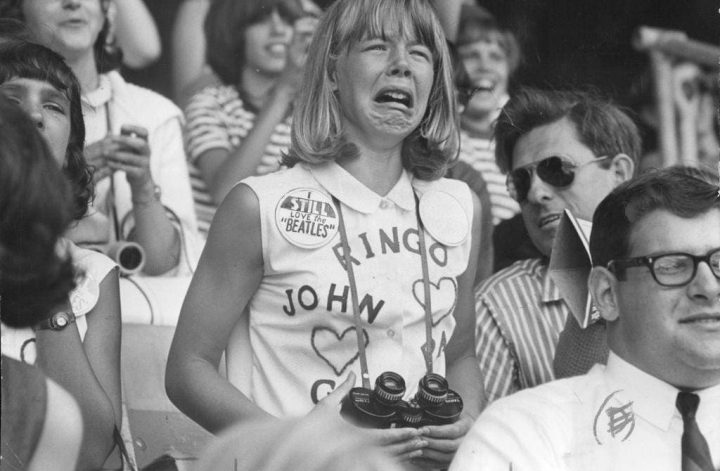

I’m woman enough to admit that I take ownership of an extreme bias when it comes to Blonde on Blonde. Often, I’ve been dismissed as nothing more than a fangirl, but in my opinion, Blonde on Blonde is Dylan’s most enduring album; a perfect conglomeration of everything there is to love about Bob Dylan – the man and the musician.

There’s moments of rambunctiousness, countered with poetic elegance; it’s chaotic in places and measured in others – with exemplary music and wonderful Dylan quirks that make Blonde on Blonde a worthy listen time and time again.

Dylan offers a spontaneous giggle in Rainy Day Women #12 & 35, stumbles over his words in I Want You, is viciously scathing in Leopard Skin Pill Hat, and concludes the album with a heartfelt epic, 11-minute love poem in Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.

The passion that lies in even the smallest of Dylan’s intonations throughout the album ensures that Blonde on Blonde can never be listened to in the same way twice.

Blonde on blonde: the rumour mill

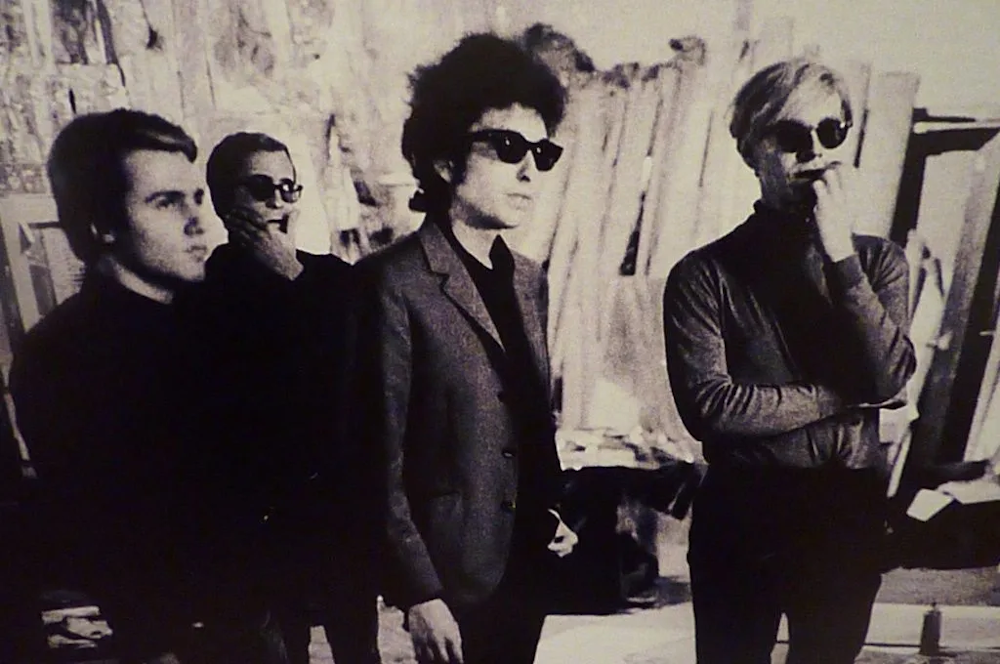

Since its release in 1966, Blonde on Blonde has been synonymous with Andy Warhol, his factory and his superstar, Edie Sedgwick. While he’s never admitted this, there are a multitude of songs and references on the album that place Dylan central in the fancy free, hedonistic world that Warhol and Sedgwick’s relationship created – and it certainly didn’t go unnoticed:

I don’t know how she did it. Fire

– Patti Smith

she was shaking all over. It took

her hours to put her make-up on.

But she did it. Even the false eye-lashes.

She ordered gin with triple

limes. Then a limousine. Everyone

knew she was the real heroine of

Blonde on Blonde.

Read the full poem here.

There are countless books, essays and social commentaries that attest to Dylan’s involvement with Edie, but to what extend their relationship developed remains unknown. One thing that I am relatively certain of, however, is that Blonde on Blonde would not have been the same without the factory girl.

Bob Dylan’s factory girl

Edie Sedgwick established herself as one of Andy Warhol’s most famous and most controversial muses. Edie was a superstar; a beautifully gamine individual who set the New York social scene on fire almost as soon as she arrived. Edie was enigmatic, interesting, endlessly beautiful and the name on everybody’s lips. A must meet individual. It seems doubtful, to any of the players in New York’s cultural zeitgeist at the time, that anyone could resist Edie Sedgwick’s irrepressible charms.

Including Bob Dylan.

Bob Dylan is said to have met Edie Sedgwick in 1965, when Dylan was already in a relationship with future wife Sara, and allegedly, still involved with Joan Baez (see: Don’t Look Back). Despite this, a relationship was rumoured to have developed with Edie, and she was believed to be smitten.

Blonde on Blonde isn’t all about Edie

While the major themes of Blonde on Blonde suggest Edie Sedgwick had a heavy influence on the music, there are other women mentioned on the album. After all, it’s no secret that women have often played a central role in music and songwriting, and Bob Dylan is no exception.

Visions of Johanna is alleged to be about Joan Baez, during the time he was also falling in love with his future wife, Sarah Lownds. This is juxtaposed with Dylan’s transition from folk to electric in 1965.

Listening to the track, it makes sense, given the melancholic tone and the nature of his relationship with Baez. Her influence on Dylan’s career was evident. His reference to William Blake’s little boy lost indicates an internal questioning about his relationship and his identity: could Dylan make a successful transition to electric with Baez by his side?

Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands is undoubtedly about Sara, as confirmed in the 1975 track of the same name:

Staying up nights in the Chelsea hotel,

writing Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands for you

The lyrics in 1966’s Sad Eyed Lady are bursting with complex imagery focused heavily on religion, which has opened up debate about the song’s true meaning.

Personally, I feel that the references to ‘waiting’ and ‘standing at gates’ indicates Dylan feeling trapped. There are three women central to Blonde on Blonde and while he loved Sara, there was something holding him back. This could have been Joan Baez, his transition to electric, his career’s success or indeed, Edie Sedgwick, Blonde on Blonde’s girl on fire.

Bob Dylan wants Edie

Bob Dylan’s relationship with Edie Sedgwick indicates a passionate beginning and a harrowing end. Written with the benefit of extreme hindsight, Blonde on Blonde features songs alleged to be about Edie that are passionate, contradictory and inflammatory in imagery that refuses to put the Edie and Dylan rumour to bed, no matter how often he has tried.

I Want You

The opening bars make I Want You feel like a jaunty tale of discovery, ostensibly depicting the introductory moments of Edie and Dylan’s relationship – when Bob Dylan was drawn into the frenzied world within Warhol’s silver-sprayed factory.

The first stanza implies that Dylan was warned away:

The guilty undertaker sighs/the lonesome organ grinder cries/the silver saxophones, say I should, refuse you.

This suggested that people within the factory (namely ‘the silver saxophones’) warned Dylan against Edie. However, as the stanza draws to a close, there’s an admission of determination to be with Edie, on Dylan’s part:

I wasn’t born to lose you.

The dancing child in his Chinese suit alludes to Andy Warhol himself (as in Like a Rolling stone, he’s referred to as Napoleon in rags). The taking of the flute, refers to Dylan’s first visit to the factory, with Warhol supplanted as the pied piper, so to speak.

If you’ve seen Dylan’s screen test, you can understand that I spoke to him, I took his flute suggests that Dylan and Andy’s respective relationships with Edie caused tension in the factory.

I wasn’t very cute to him, was I?

The following: I did it because he lied/because he took you for a ride/because time was on his side pertains to the exploitative nature of Warhol and Edie’s relationship, which Dylan resented him for. This, coupled with the slight trip up over his words before ascending to the chorus, almost confirms Dylan’s frustration with the nature of Andy Warhol’s relationship with Edie.

Further, there’s a seemingly implicit admission of his affair with Edie, suggesting that Sara knew:

Well, I return to the Queen of Spades

And talk with my chambermaid

She knows that I’m not afraid to look at her

She is good to me

And there’s nothing she doesn’t see

She knows where I’d like to be

But it doesn’t matter

In this stanza, I think both the Queen of Spades and the chambermaid refer to Sara Lownds. While they both offer opposing meanings – Queen of Spades evoking imagery of power and authority, while chambermaid being more literal – both incorporate elements of Dylan’s relationship with Lownds.

She was an authoritative figure in his life, and she was, as crass as this is, his chambermaid; the woman with whom he was supposed to share his bed.

I’m not afraid to look at her implies that both were aware of the infidelity and Dylan was not interested in stopping his affair.

Just Like a Woman

Just Like a Woman is one of the most important songs on Blonde on Blonde. It’s unashamedly revealing and the tension and frustration is almost palpable. Bob Dylan is at odds, and the song feels like a one-sided argument; a vocalised relationship that the woman he fell for isn’t the one he wants to be with, after all.

The first stanza offers an indication of tension and a realisation that only Dylan can see:

Lately I’ve seen her ribbons and her bows/have fallen from her curls.

This suggests that the ‘baby’ figure with her new clothes, has fallen from Dylan’s good graces – a fall from grace further indicating religious imagery in Blonde on Blonde, which is seen in the following stanza. The first iteration of the chorus, suggests that despite trying hard to be a grown up; a woman, Edie is fundamentally still juvenile, because she breaks just like a little girl.

The second stanza opens with reference to Queen Mary. This is the second mention of a ‘queen’ in Blonde on Blonde. Coupled with a fall from graze, in this instance, Queen Mary suggests that Dylan is making reference to Sara Lownds. I think I’ll go see her again indicates a break up between Dylan and Edie, with the more mature Lownds being a more appropriate option for Dylan’s image and his career.

This is amplified by the lyric nobody has to guess that baby can’t be blessed/’til she finally sees that she’s like all the rest. Whether Dylan is implying ‘the rest’ as in, the people Edie hangs out with at Warhol’s factory, or that there’s nothing special about her as a woman, is up for debate.

My belief is that with her fog, her amphetamine and her pearls, Edie Sedgwick isn’t good for Dylan’s image or his career, and unless she’s willing to leave Andy Warhol’s factory, they can’t be together.

So he makes a decision to return to Sara.

This makes the penultimate stanza quite poignant; it feels that there’s an emotional struggle on Dylan’s part. He understands baby/Edie’s long time curse – which refers to her lifelong battle with eating disorders and depression – indicating that Dylan is conflicted.

I can’t stay in here/ain’t it clear/that I just can’t fit amplifies his conflict, suggesting that while he loves Edie, the relationship is toxic for various reasons. However, the final stanza offers a contradiction – cruel, almost:

When we meet again

Introduced as friends

Please don’t let on that you knew me when

I was hungry and it was your world

I was hungry and it was your world is offensive; it suggests that Dylan used Edie’s position as New York’s It Girl to amplify his career and reputation. The stanza suggests that once he leaves Edie to go back to Sara that they will become strangers, as though he wants to forget the tryst entirely, further fuelling the flames that Dylan used Edie.

The final chorus seems to spit a new found disdain for Edie that Dylan has not yet established, muddying the waters once more: you fake just like a woman implies that Edie has been disingenuous, and isn’t behaving in a manner that is true to herself, which was indicated earlier with Edie’s ‘fog’.

Ultimately, this song suggests to me that Dylan’s complex and tense relationship with Andy Warhol is why he and Edie can’t be together; her reticence to leave a scene that has been nothing but good to her, to be Bob Dylan’s girlfriend, seems to be a big pain point for Dylan, which is harrowingly relevant in the next song.

Leopard Skin Pill-Box Hat

This is a song that is overtly raw, and suggests that Dylan was hurt by Edie. The lyrics are spat out with scorn; a far cry from other Edie specific songs on Blonde on Blonde.

Leopard Skin Pill-Box Hat is accusatory to those who subscribe to the materialism and superficiality of fashion. This is reinforced by the repetition of ‘brand new’ throughout.

This is an obvious reference to Edie, New York’s It Girl and obvious slave to fashion. The suggestion is that she is vapid and ridiculous: you know it balances on your head/just like a mattress balances/on a bottle of wine.

The second stanza of Leopard-skin Pill-box Hat indicates that the rumour mill is to be believed:

Well I asked the doctor if I could see you

It’s bad for your health, he said

Yes, I disobeyed his orders

I came to see you but I found him there instead

You know, I don’t mind him cheatin’ on me, but I

Sure wish he’d take that off his head

Your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat

Edie’s increased use of amphetamines was a big reason for the demise of her relationship with Dylan, as referenced to in Just Like a Woman. At the time, Bob Dylan’s best friend Bob Neuwirth was heavily involved in Dylan’s career, so the suggestion here would be that the ‘doctor’ tried to prevent Dylan from seeing Edie because she was ‘bad’ for his career.

I disobeyed his orders indicates that despite this, Dylan went to see Edie, only to find him there instead. The rumour mill suggested that when Edie and Dylan’s relationship ended, Neuwirth pursued a relationship with Edie instead. As such, Dylan doesn’t blame Edie for cheating, but his former best friend, Neuwirth – the betrayal lies with him, but the scorn remains for Edie.

One of us Must Know

This might be my favourite track on Blonde on Blonde. Its veiled poignancy ultimately reveals an almost complacency on Dylan’s part, towards his relationship with Edie, and despite the romantic overtones, delving into the lyrics of One of us Must Know reveals that it’s not all that romantic.

The introductory stanza:

I didn’t mean to treat you so bad

You shouldn’t take it so personal

I didn’t mean to make you so sad

You just happened to be there, that’s all

This echoes Just Like a Woman in the sense that Edie just happened to be there, that’s all. In Just Like a Woman Dylan was ‘hungry’ and it was Edie’s ‘world’. In One of us Must Know, the suggestion is that had Edie been anyone else, it wouldn’t matter.

Yet, the repetition of I didn’t mean in this stanza, implies that Dylan may, to some extent, feel guilt towards what transpired between him and Edie, even if in the closing statement, he implies he’s excusing his behaviour.

The latter part of the first stanza seems to resolve a misunderstanding; while Dylan thought Edie was unable to remove herself from Warhol and his world, she actually proved Dylan wrong:

When I saw you say ‘goodbye’ to your friends and smile

I thought it was well understood

That you’d be comin’ back in a little while

I didn’t know you’d be saying ‘goodbye’ for good

The chorus reveals further that Edie played a role in Dylan’s career, she was doing what she was supposed to do – amplifying his position in the New York social scene – and helping him further his career. This is repeated in the second stanza, which reveals that Dylan didn’t take his relationship with Edie seriously; that she was a means to an end.

The second stanza almost contradicts what we’ve heard so far, implying that Dylan may feel some guilt in his treatment of Edie. The assumption was that she understood the role she played, with even the suggestion that Sara Lownds understood that Dylan’s infidelity was for the benefit of his career – the only person who didn’t understand was Edie:

When you whispered in my ear

And asked me if I was leavin’ with you or her

I didn’t realise what I did hear

I didn’t realise how young you were

An echo to Just Like a Woman, in the fact that Edie was playing grown up games without realising it. The revelation that Edie genuinely believed that Dylan would leave Sara to be with her.

The final stanza seemingly reiterates the breakdown of their relationship, as per Just Like a Woman, but also introduces themes, later to be seen in Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands. Namely, with reference to Edie growing up on an enormous ranch, in a similar manner to Sara – however, this could also be a reference to The Chelsea Hotel. Dylan could be suggesting that Edie didn’t truly belong; in Andy’s factory, the New York social scene, or in Dylan’s life and career.

The final reiteration of Dylan’s ambivalence towards the Edie situation is in the lyric, An’ I told you, as you clawed out my eyes/that I really never meant to do you no harm. This concludes his involvement as ‘done’. Dylan has acknowledged that he was simply acting as though Edie was complicit, and that her heartbreak was as a result of her age, her immaturity, rather than Dylan openly admitting he used her for his own gain.

Blonde on Blonde: an album

In my opinion, Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde should never be too far from anyone’s record player. It offers not only an album full of tracks that stick with you, long after listening, but also offers an insight into the life and times of Bob Dylan during the roaring sixties, as part of the most pivotal New York social scene of all time.

Rather than your thoughts and feelings on the matter, the true genius of Blonde on Blonde lies in the fact that no one, other than Bob Dylan himself, will ever know the meaning behind the songs, thus, they are forever open for interpretation.

It’s also an inadvertent eulogy for one of my favourite women of the time. Even if I’m looking too much into it.

In short, Bob Dylan is a genius, and Blonde on Blonde will never be too far away from my record player.